km od začátku : 0017

Isurava

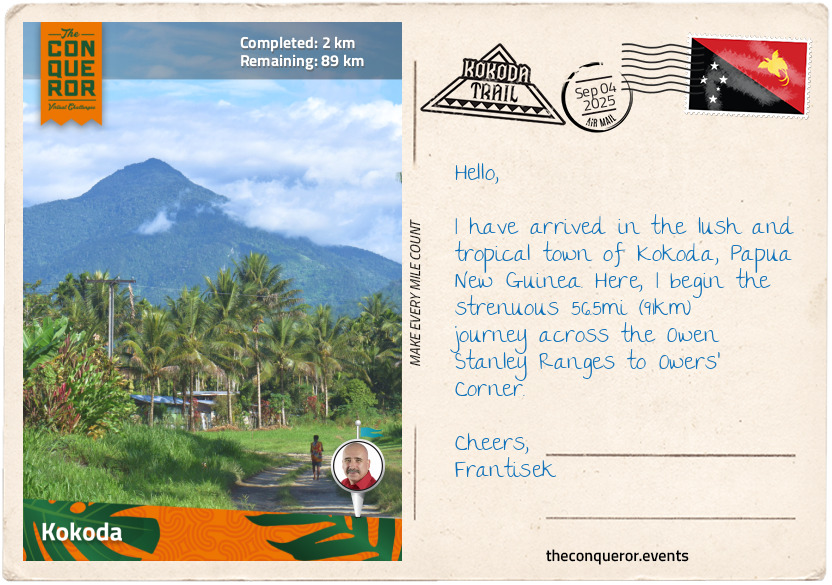

My trek to Kokoda began at an elevation of 984ft (300m) above sea level. Heading up an old tractor track, through a rubber plantation, after only 2mi (3.5km) I reached Kovelo Village located in an open clearing with houses scattered around the edges.

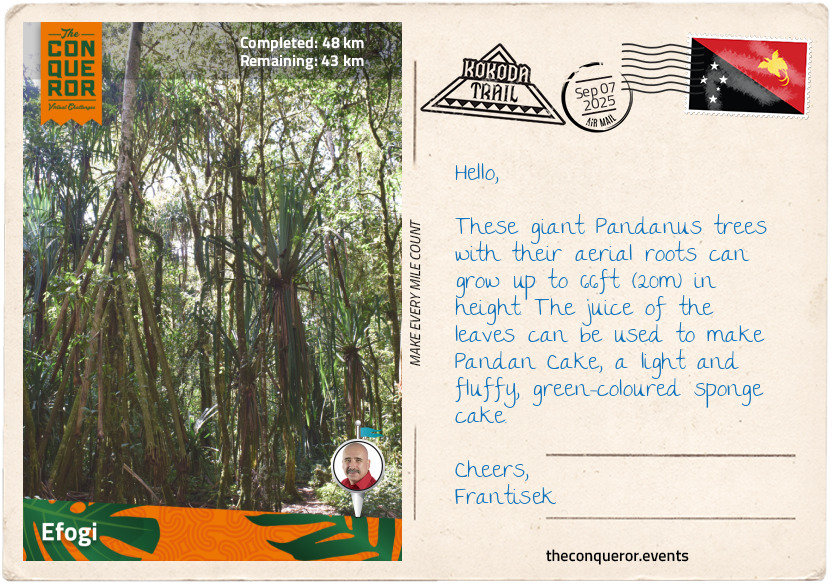

After a brief rest, I entered the jungle via a single track and began climbing. A mist hung over the jungle, making the tropical heat more bearable. Densely forested, the track was wet but at least it wasn’t boggy. I could feel the elevation gain. Every now and then, I would stop to rest my burning calves.

Surfacing from the jungle into another clearing, I arrived at Deniki, a small village that sat at an elevation of 2,624ft (800m). Being on higher ground, Deniki opened to views of Yodda Valley on the north side of Owen Stanley Ranges and the Kokoda airstrip in the distance.

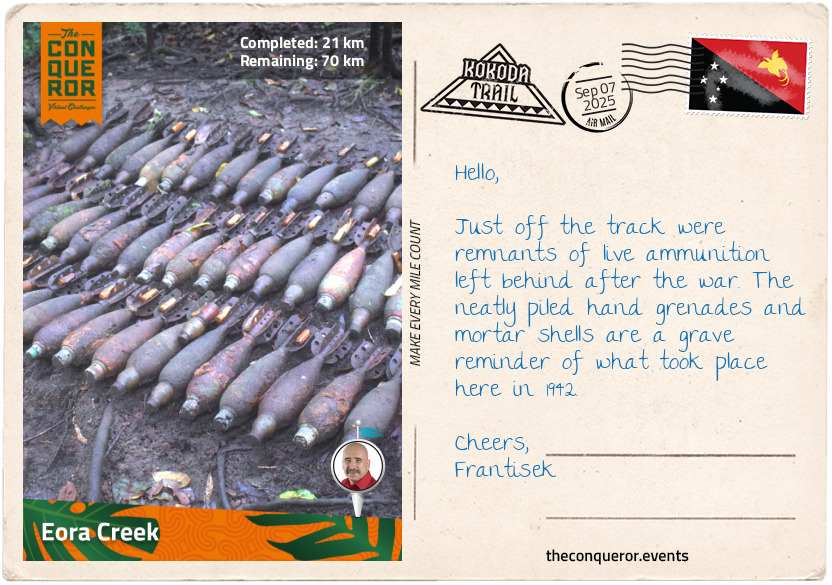

In late July 1942, Kokoda was the scene of a number of small but intensely fought battles. The Australians (Aussies) were waiting for reinforcements to be flown in but upon hearing that another Aussie company was overrun in Oivi (north of Kokoda) they gave up Kokoda and retreated to Deniki. They returned to Kokoda the next day with a force of about 80 men but once the Japanese were reinforced, they attacked the Aussies the day after. The Aussie troops withdrew yet again to Deniki. Joined by other companies, the Aussies tried to take Kokoda once again but were unsuccessful. Tired and short of food, by mid-August the Aussies withdrew to Isurava. It would take another three months (until November 1942) before the Aussie forces returned to Kokoda during their counter-offensive.

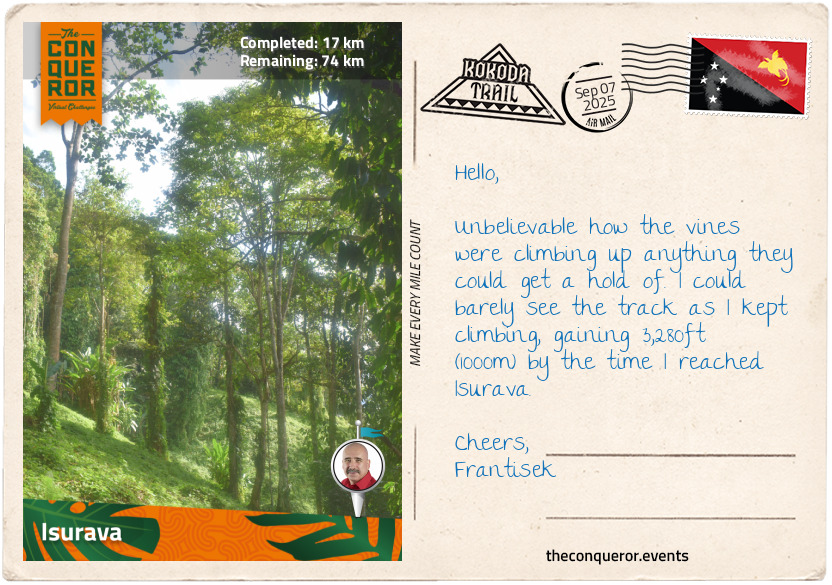

Okari trees grow around Deniki. They are a small mid-canopy tree with edible nuts very similar to almonds. Tucking a couple of them in my pocket, I pressed on and wondered at the same time at the massive vines taking over the abandoned native gardens. As I climbed up a steep, mostly clay track, I saw more vines spreading through the jungle and up the trunks of trees, seemingly wanting to conquer all plant life.

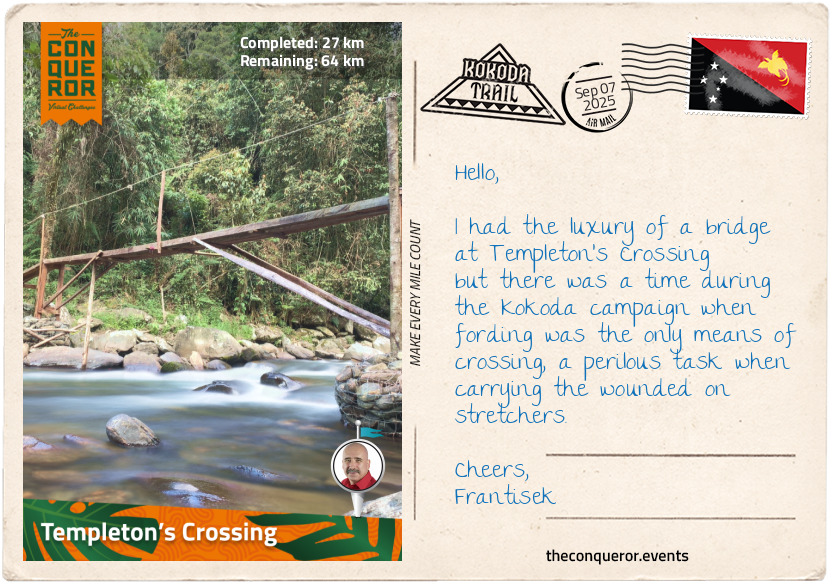

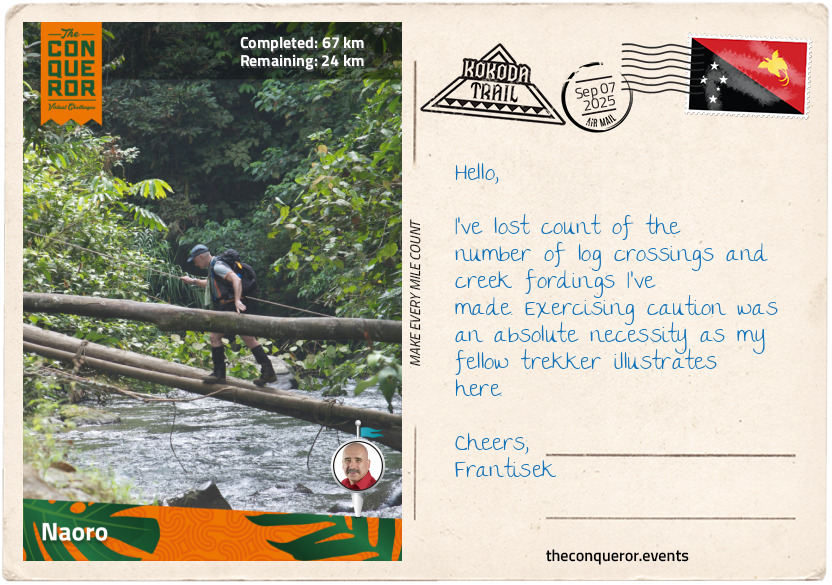

The trail continued on its upward trajectory, with several creek crossings and a couple of false peaks before I arrived at Isurava Village, the site of the Battle of Isurava, where Australian forces resisted the Japanese offensive. Up against machine-gun fire and hand-to-hand combat, the Japanese broke through the Aussie right flank. An Australian attack party countered when Private Bruce Kingsbury, shooting from his hip, charged the Japanese, either killing or scattering them, giving the Australians sufficient time to regain control and stabilise their position. Mortally wounded by a sniper, Kingsbury was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s most prestigious award for valour “in the presence of the enemy”. In 1991, Australia established its own Victoria Cross award.

The Isurava Memorial was opened in 2002, commemorating those who died on the track in 1942. The circular Memorial consists of four black granite sentinel stones, each inscribed with a single word - Courage, Endurance, Mateship, Sacrifice - representing the values and qualities of the soldiers. Incorporated into the Memorial is Kingsbury’s Rock, the location where Kingsbury died.

Holding these four words close to my heart, I took some time at the Memorial, pondering the battle and the men who fought it.

Photo ©

Jonty Crane