km od začátku : 0061

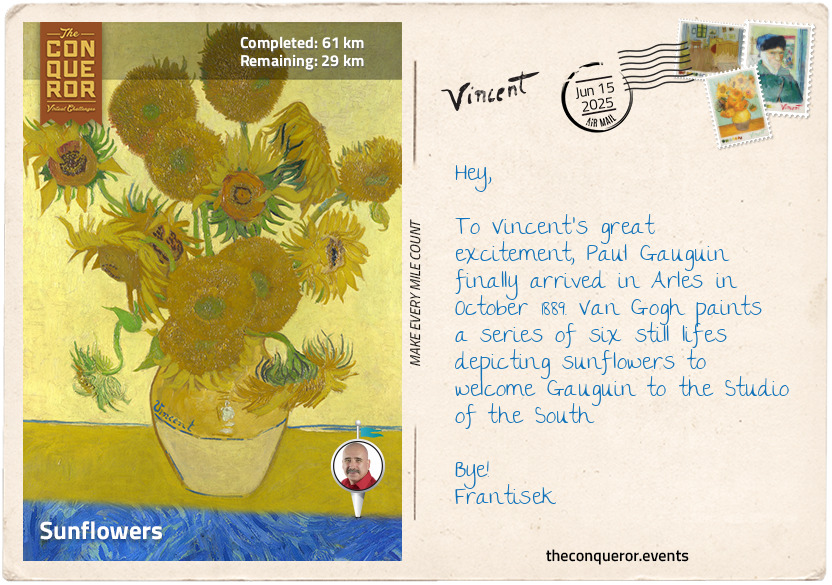

Sunflowers

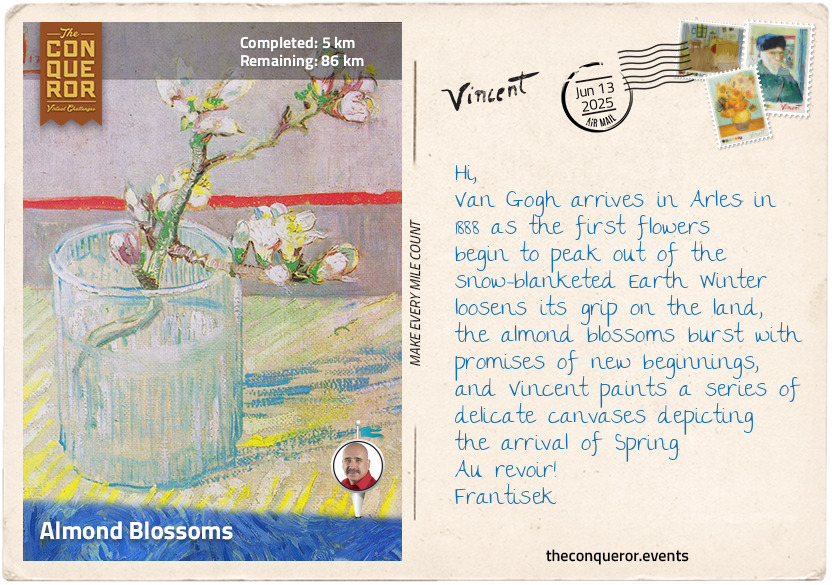

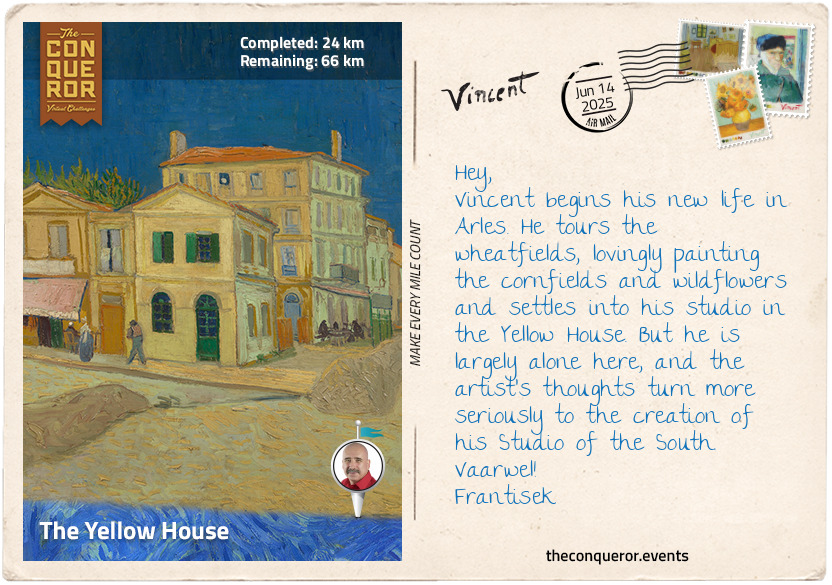

Paul Gauguin, Vincent’s great hero and mentor, has agreed to come to Arles to live in the Yellow House and to begin the formation of the Studio of the South. In a letter to Gauguin sent just before his arrival, the artist’s excitement is palpable, he reassures Gauguin he won’t miss Paris, he describes an ‘extraordinary fever for work’, he frets that he has come too late in the year and that he will have to be patient before he sees the true beauty of the Provençal landscape.

To Vincent, yellow was more than one of his favourite colours; it represented truth, happiness and divinity. Further, to the Dutch, yellow was the colour of loyalty and devotion, a symbol to Vincent of his commitment to art and like-minded artists. To welcome his friend, Vincent painted six still-life sunflowers, with which he decorated Gauguin’s room in the Yellow House. The paintings are a celebration of yellow and exude optimism, lightness, a playful, happy attitude, and a sense of welcoming camaraderie.

But it’s also a painting of formal experimentation - Van Gogh’s predecessors, the Impressionists, had stressed that the best way to make your colours more vivid was to place contrasting hues next to each other (colours on the opposite parts of the colour wheel). This creates a kind of visual vibration that heightens the colour’s intensity. Here, Van Gogh does the opposite: he puts yellow against yellow, the yellow sunflowers stand against a light yellow background; we have three shades of yellow and almost nothing else, and it works! The painting practically radiates golden light. Gauguin was immediately impressed with the series, describing the paintings as ‘completely Vincent’.

Gauguin would stay with Vincent for nine turbulent weeks. At first, the two get on well: they spend their days in the studio or the fields. Gauguin creates some of his most famous works here, including his portrait of Vincent, The Painter of Sunflowers, which depicts him leaning back into the right of the frame, decked out in yellows upon yellows, painting a bunch of sunflowers on his table (see link at the bottom of the postcard).

However, the two men were strong personalities with strong opinions on how art should be approached. Soon, serious differences began to crop up between them. They agreed on what they saw as the somewhat decorative, shallow works of the Impressionists, on the need instead for symbolism and expression in their work, and on the joys of drinking absinthe long into the night. When it came to virtually everything else, they were at loggerheads.

Foremost, Vincent took issue with Gauguin’s preference for painting from memory or imagination, using the natural world only as a starting point. Vincent believed that the truth and depth of the work came from nature, which spoke to the artist through direct connection and observation. Like the Impressionists, he aimed to capture the immediate experience of his subject - the fleeting feeling a landscape, a person or an interior invoked - a feeling he believed could only be captured if his subject was grounded in reality.

Gauguin, on the other hand, had a more intellectualised approach. He saw the use of the imagination as a way to reveal deep, inner truths. Inspired by the abstract forms of non-Western art, he created canvases saturated with dreamlike motifs and esoteric symbolism, ending up with paintings filled with imaginary patterns, figures and landscapes.

Gradually, the two realised that they had unreconcilable differences. There would be no community of kindred spirits working together to create a new artist’s colony bathed in Provençal light. Vincent and Gauguin simply could not get along.

Gaugin and Vincent’s relationship was healthy, productive and strong at first. Like the sunflowers in the vase, they radiated beauty and golden light. But over time, sunflowers wilt and whither. One by one, the petals drop, the stem droops, the head falls into the mulch, and what was once perfect becomes rotten. An icy chill had settled into the Yellow House that winter. Their friendship was going the same way as the sunflowers Vincent bought to paint back in October, freezing over in the December frost.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Painter_of_Sunflowers#/media/File:Paul_Gauguin_-_Vincent_van_Gogh_painting_sunflowers_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg